New year, fresh goals. Once more, that moment has come. According to a recent poll, about 58% of the UK population, or around 30 million persons, planned to make a new year’s goal in 2023. More than a quarter of these objectives will center on enhancing one’s financial situation, improving oneself, or decreasing weight.

Will we succeed, though? Sadly, a study of over 800 million events by the fitness tracking app Strava indicates that the majority of these commitments will be broken by January 19.

Because they are ambiguous, promises frequently fall through before the end of January. They emphasize intangibles like improved health, more happiness (without specifying what that entails), and increased wealth (without coming up with an amount or plan).

We cannot adequately lead ourselves with hazy objectives. It is challenging to choose a course of action when we are unsure of our specific destination. It is hard to predict how far we still have to travel, what obstacles we will face, and how to best prepare for them.

To push ourselves, we frequently establish impossible objectives for ourselves. The “effort paradox” refers to the inherent contradiction between how much our brains enjoy the concept of effort and how unpleasant it makes us feel. We would want to believe that pushing ourselves to accomplish a challenging objective will make us feel more content.

We feel cut off from our future selves and are predisposed to the present, which is another cause for this. This implies that we have a hard time imagining the kinds of challenges our future selves would encounter while attempting to carry out our resolutions.

The slothful mind

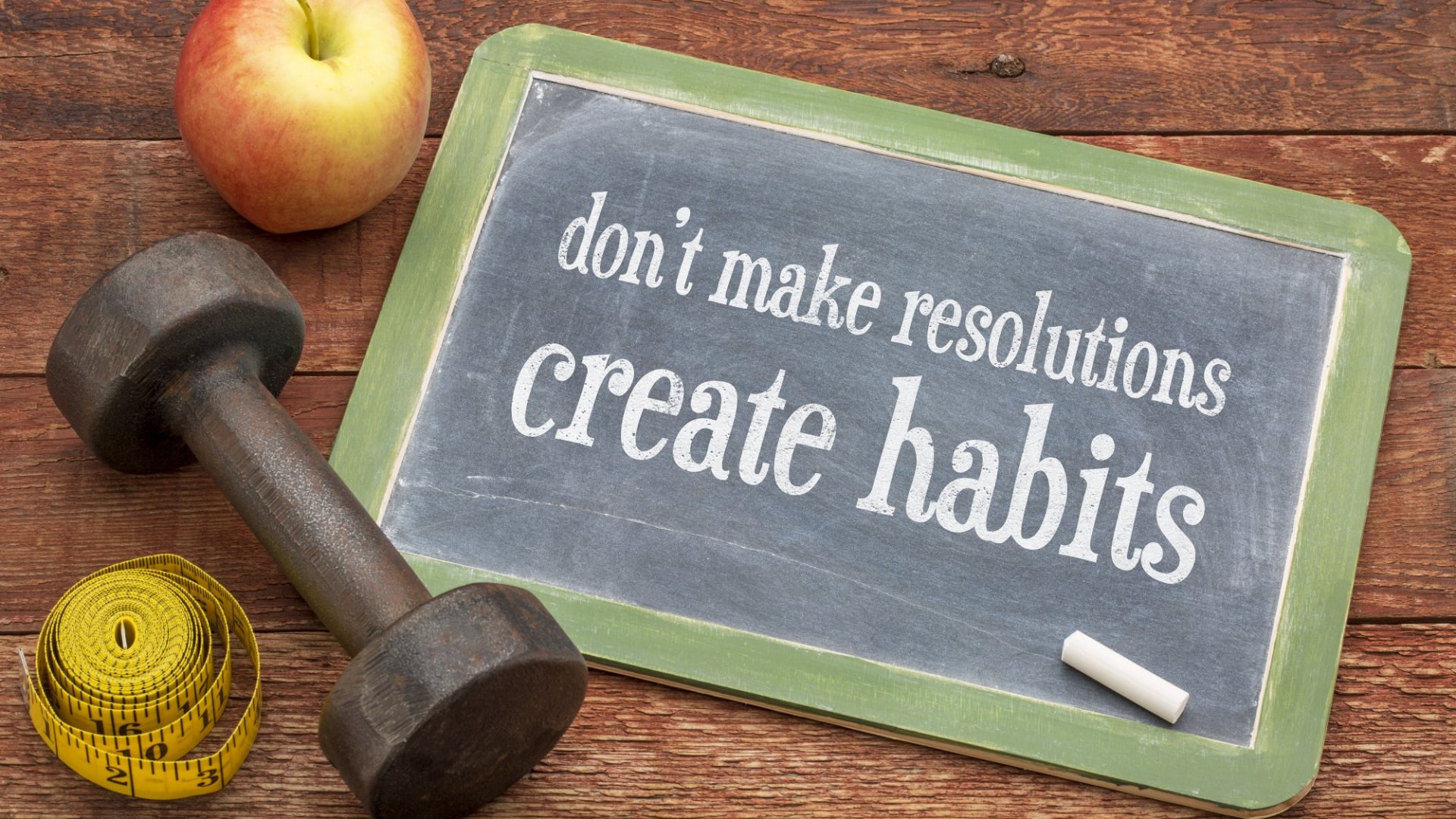

We create habits by developing mental shortcuts to help us navigate the world. When these mental shortcuts are ingrained into our brains, it becomes simpler to behave without much thought or control. The cognitive shortcuts that underlie these behaviors become more firmly ingrained the longer we have them.

For instance, it can become usual for us to go for the biscuit jar when we park ourselves in front of the television at night. Or, when the alarm goes off in the morning, we press the snooze button.

Because of our brains’ laziness and desire to reduce cognitive burden, we repeat activities that give us pleasure rather than thinking through a wide variety of possibilities, some of which may be more or less enjoyable.

Simply said, it is simpler to use these shortcuts when there is less resistance or suffering. Though some people may find it more difficult to change bad habits than others since they rely on them more than others.

But to keep our resolutions, we frequently need to shift these ingrained behaviors and the corresponding brain connections. We are inclined to return to a more familiar area, yet our brains fight this discomfort. This is the reason we abandon our resolutions. The status quo bias is one facet of this. We are more inclined to maintain the status quo—our current viewpoints—than to keep trying to change these behaviors, which requires time and energy.

The more we concentrate on the result rather than the small steps required to get there, the harder it will be to alter our perspectives and establish the habits required to get there. The more anxious we grow about something, the more probable it is that we will revert to our cognitive shortcuts, creating a vicious cycle.

Areas of the back of the brain associated with automatic behavior are usually active when we engage in habits. However, we need to activate numerous parts of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex, which is engaged in extremely difficult cognitive tasks, to actively change our neural pathways away from such activation.

Better methods

Being aware of the behavioral patterns we have ingrained through time and realizing how difficult it is to change them are prerequisites for changing habits. And if you are seeing just the brand-new, ideal version of yourself, that is impossible. But to successfully change oneself, you must be aware of your true self.

Setting specific, attainable objectives can also be useful. For example, you can decide to devote an additional hour a week to your favorite pastime or restrict yourself to eating biscuits only in the evenings in favor of a good cup of herbal tea.

Additionally, we must recognize and celebrate the progress we have made toward our objectives. Many of us tend to concentrate on the unpleasant parts of the event, which can cause tension and worry. Negativity bias refers to the tendency for negative emotions to demand greater attention. And the more we dwell on the negative elements of our lives and ourselves, the more probable it is that we will feel depressed and miss the good things.

The more we put our attention on what we enjoy in ourselves, the easier it will be to shift our thoughts.