The unborn child was in difficulty. A UK hospital’s physicians chose to conduct an emergency C-section many weeks before the baby was due since they sensed there was something wrong with the fetus’s blood. However, despite this and more blood transfusions, the infant experienced a brain bleed that had grave implications. It tragically died.

The cause of the hemorrhage was unclear. However, there was a hint in the mother’s blood, where medical professionals had found some odd antibodies. A sample of the mother’s blood came from a lab in Bristol run by experts who study blood groups sometime later when the medical professionals were attempting to learn more about them.

They found an unexpected finding: The woman’s blood type was ultrarare, which would have rendered her child’s blood incompatible with her own. This likely caused her immune system to manufacture antibodies that were harmful to her unborn kid and ultimately caused its death. These antibodies may have been produced in response to the blood of her unborn child.

Although it may seem unlikely that such a thing could occur, it happened rather frequently many years ago, when doctors had a better grasp of blood kinds.

Scientists were able to determine exactly what made the mother’s blood distinctive by examining it together with many other blood samples. In the process, they validated a new system of blood grouping—the “Er” system, the 44th to be defined.

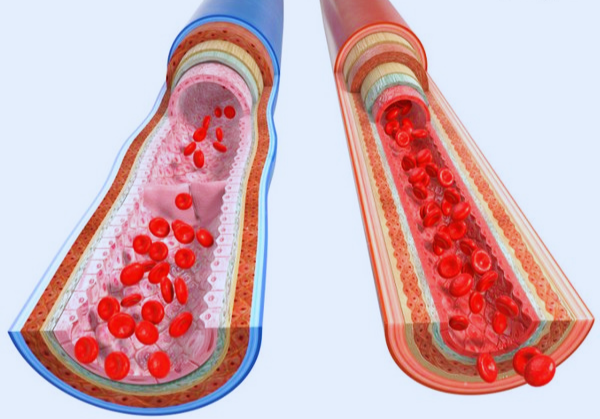

The four primary blood types—A, B, O, and AB—are presumably already recognizable to you. However, this is not the sole technique for categorizing blood. Based on variations in the sugars or proteins that cover the surface of red blood cells and are referred to as antigens, there are several ways to classify red blood cells. Your blood can be categorized using any of the grouping methods since they operate simultaneously; for example, type O in the ABO system, positive (rather than negative) under the Rhesus system, etc.

Because antigens differ, if someone obtains incompatible blood from a donor, their immune system can mistake the antigens for foreign substances and mount an attack. Because this may be extremely harmful, donated blood must be a good match.

Researchers initially discovered an uncommon antibody in a blood sample in 1982, providing evidence that an unidentified blood type existed. The researchers recognized that the antibody was a sign pointing toward an unidentified chemical or structure that caused the person’s immune system to produce it, but they couldn’t go much farther than that at the time.

More cases of these unique antibodies appeared in the years that followed, although only occasionally. These individuals often came to light as a result of blood testing that revealed odd and uncommon antibodies. Nicole Thornton and her coworkers at NHS Blood and Transplant in the UK ultimately decided to investigate the potential causes of the antibodies. We work on uncommon instances, she claims.

The process begins with a patient who has an issue that we are attempting to fix. However, the strange antibodies in the most recent research were so uncommon that when the team’s analysis got underway, they only had historical blood samples from 13 people—collected over 40 years—to examine. Similar modest groups of people have helped uncover other recently developed systems. In 2020, Thornton and her coworkers introduced the MAM-negative blood type, which at the time had just 11 verified cases globally. Additionally, she notes, some of the most recent blood types have been detected in single families.

The letters “MAM” and “Er” are both cryptic allusions to the names of the patients whose blood samples originally raised the potential of discovering a new blood type.

The International Society of Blood Transfusion conference later this year is anticipated to formally ratify the study’s findings as designating a new blood group system. The amount of labor necessary to achieve the finding was “huge,” according to Neil Avent, an honorary professor in the University of Plymouth’s blood diagnostics section who was not involved in the research.

“Learning about a new blood group system is like learning about a new planet. It broadens the scope of our experience, adds Saint Louis University School of Medicine’s Daniela Hermelin, who was not involved in the study. She says it increases our understanding of the potential effects of blood incompatibility on expectant moms and their unborn children. And now that cases of blood incompatibility may be linked to the Er blood group, it improves the likelihood that clinicians will be able to accurately identify and treat such a condition, such as by providing the infant a blood transfusion while still in the womb.

Bottom Line:

According to Avent, it’s quite improbable that you would be incompatible with someone else’s blood because of Er antigens. If you do, though, you should be aware of it. It also highlighted the complexity of this unusual blood, such as the fact that it is linked to several genetic abnormalities.